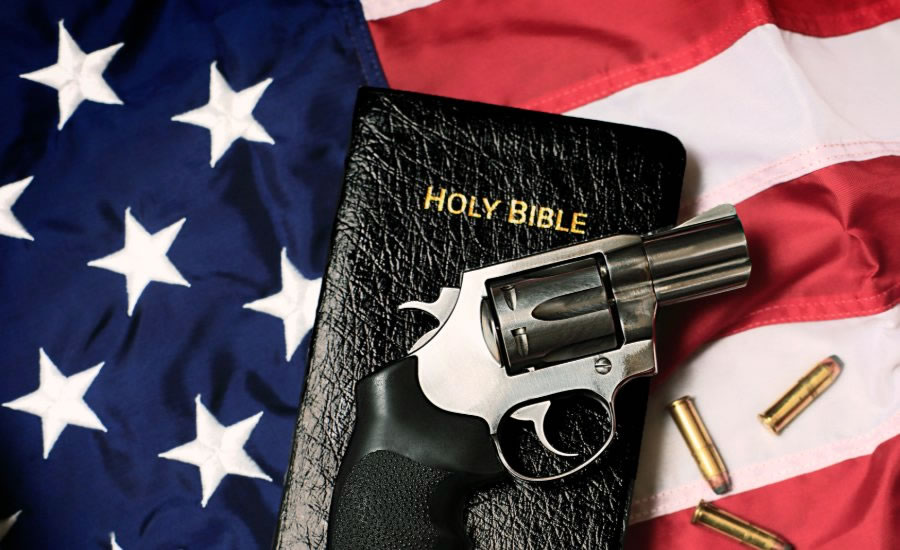

Protecting Religious Freedom Is the First Reason for Gun Rights. The Historical Record Is Clear

I’ve written about it here in thumbnail version before: The constitutional guarantee of gun rights for Americans traces back to our Founders’ concern for religious freedom. Yes, for political liberty, a free press, representative government, the protection against arbitrary and corrupt tyranny — such as most governments that have ruled most human beings throughout our fallen history. All of that is true. But the link between gun rights and religious freedom is even more direct. In fact, it’s blindingly obvious.

In my series so far, I’ve traced in detail the gradual emergence of religious liberty in the West, especially the English-speaking world. Most recently, I showed how the victory of Parliament over the Divine Right of Kings in Britain was driven largely by concerns of low-church, “dissenting” Protestants that the Anglican Church would continue or escalate its repression. Or that the Catholic-friendly Stuarts might even restore links with Rome, and impose Catholicism on Britain by force.

Mutual Persecution of Churches

Now, the latter fear was certainly overblown. Catholics endured the worst religious persecution of any minority in Britain. (The Jews had been expelled in the late Middle Ages.) Decades of royal propaganda had convinced most Britons that Catholics wanted “foreign” domination of their island, and were uniquely disposed to hunting and burning “heretics.”

Please Support The Stream: Equipping Christians to Think Clearly About the Political, Economic, and Moral Issues of Our Day.

In fact, both Protestants and Catholics had been equally fervent in persecuting each other on English and Scottish soil. Henry VIII had brutally seized the lands and vandalized the buildings of England’s monasteries, which for centuries had been the only educators and charitable agencies for the poor. He had burned alive, beheaded, and otherwise slaughtered Catholics. His son, Edward VI, led by Calvinist advisors, had continued the persecution.

It was interrupted by Mary’s brief reign, which persecuted Protestants — whose fate was enshrined in popular books such as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. When Mary died childless, Elizabeth I resumed the hunting of “papists,” and established a secret police to hunt down exiled priests who came back to England. They were branded not as “heretics” but “traitors,” and loyalty to Protestantism was cast as a patriotic duty. Nevertheless, such priests were executed by the most hideous means: being hanged up alive, their entrails drawn out of them, then pulled into four pieces (quartered), sometimes by horses.

The Ongoing English Reformation

What won English Protestants over to talk of even partial religious freedom? The fact that the Reformation continued in Britain, creating variants of Christian belief and worship that were much more radical than the Anglican compromise — which the monarchs kept trying to enforce. So Anglican kings such as James I and Charles I at once repressed both Catholics and “Puritans,” whose Calvinist theology and proto-democratic structure didn’t fit the Anglican monarchs’ program. As I wrote in my last installment, this conflict helped fuel the English Civil War.

That war had seemed to end with the Restoration, the return of King Charles II to resume his beheaded father’s throne. He promised a moderate regime, which would rule with consent of Parliament, and amnesty all the rebels — except those directly responsible for killing Charles I. That was the program most English were glad to accept.

Jealous of the French

But Charles wasn’t happy with it. He’d spent his exile in France, where the monarchy had become quite absolute, with a dominion over the Church not even the pope could challenge. King Louis XIV, who’d hosted and supported Charles, didn’t even summon France’s parliament. His monarchy had vast estates and funds and ruled by decree. It resolved religious dissent by simple force, revoking when it wished to the century-old toleration of French Protestants. Indeed, the vicious persecution of Huguenots shocked the pope, who loudly condemned it. But France’s king answered to no one, and thousands of French Protestants were stripped of their children (who’d be raised by others as Catholics), executed, or driven out of France.

Charles saw that his native Anglican church was by no means as powerful or pliable as the Catholic church in France. He married a French Catholic bride, and secretly promised (in return for a stipend from France) to restore Britain to Catholicism whenever he possibly could. What is more, he lacked legitimate children, and his openly Catholic brother, James the Duke of York, was his only heir. James, too, was a friend and ally to Louis XIV — whom Protestants worldwide rightly saw as a great persecutor.

Trying to Piece Absolutism Back Together

The reign of Charles II saw a cash-strapped king trying to patch back together the resources to make his throne independent of Parliament — exactly as his father, Charles I had tried to do. He tried to repress the strain of low-church or separatist Protestant churches which had supported Oliver Cromwell. He built up a private, royal standing army, with many Irish Catholics in its ranks, to support the royal cause in case of rebellion. And most of all he attempted to disarm Puritans, Presbyterians, and other supporters of the radical Reformation. Royal representatives honeycombed Britain, seizing stores of gunpowder, rifles, cannons, and pistols, from low-church Protestants whom Charles suspected might back rebellion or resistance to his efforts.

For an exquisitely detailed picture of this royal effort to restore absolute monarchy, and its connection to gun rights and gun ownership, see Joyce Lee Malcolm’s To Keep and Bear Arms: The Origins of an Anglo-American Right. She goes back to the Middle Ages, tracing the legal duties of Englishmen to practice the longbow, and the shifting legal opinions throughout subsequent centuries about private ownership of newly invented firearms. She shows that the first definitive assertion of a basic right to possess private firearms dates to this period.

To a very specific moment, in fact. When Charles II died (converting to Catholicism on his deathbed), his throne went to his Catholic brother, James II. James promised religious freedom for all, and even tried to enlist as allies “dissenting” Protestants—offering them the same exemption from Anglican repression that he intended to offer Catholics.

A Royal Coup

But suspicion ran far too deep. James was closely allied with Louis XIV, even depending on him for financial subsidies. Louis’ hands were stained deep red with Huguenot blood, and British Protestants were terrified that James intended to use French methods to restore Britain to Rome. When his wife bore a son and ensured a Catholic succession, Protestant nobles and leaders of Parliament approached James’ Protestant daughter Mary — and her husband, William of Orange, who ruled in the Netherlands.

In 1688, the couple led the largest invasion fleet in British history from Holland across the English channel. Most of James’ army deserted him, and he fled to Catholic Ireland. There he lost a brief civil war with William, and sailed off into exile. What might surprise readers today is this: Pope Innocent XI had openly backed William’s invasion, perhaps even secretly funding it. He issued a papal medal celebrating the Protestant victory. Innocent saw James as the puppet of Louis XIV, whose clumsy persecution of the Huguenots had embarrassed the Church, and whose constant interference in the Church’s self-governance Innocent saw as a greater threat than a Protestant king for England.

The British Parliament offered William the throne — but not without imposing a long list of conditions that limited royal power, the English Bill of Rights. This document was the 17th-century answer to the Magna Carta, which conditioned the throne on the guarantee of certain basic rights. Unlike that medieval charter, it extended those rights to the population generally. And it would serve as the model, almost exactly a century later, for America’s crucial founding documents.

Precedents for America

As the Declaration of Independence would, the English Bill of Rights laid out the reasons why a monarch’s subjects (in this case, James II’s) accused him of tyranny. As the American Bill of Rights would do, the English document spelled out certain fundamental liberties which the new regime promised to respect, as the basis of its legal legitimacy.

These liberties included the free election of members to Parliament, without royal interference; a ban on a standing army in time of peace; a guarantee of fair, jury trials and reasonable bail; a prohibition on royal fund-raising without Parliament, and many other tenets which Americans would find familiar.

Guns to Protect the Churches

But the key element for us today is this one: “That the subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law.”

As Americans accustomed to, even spoiled by, the expansive religious freedom our forefathers purchased for us, we might read this provision cynically. Why is it limited to Protestants? Was it right to deny the same liberties to Catholics or Jews? But that is to ignore the historical context —which is crucial. Britain was exiting a period of religiously-motivated civil war, in which Catholic-friendly kings allied to foreign Catholic monarchs who persecuted Protestants had selectively disarmed low-church Protestants, while building royal armies of high-church Anglicans and Catholics.

This provision in the English Bill of Rights would serve as the direct inspiration of the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would make no discriminatory exceptions. The very fact that the founders of Britain’s limited monarchy in 1688 saw religious freedom as dependent on citizens’ gun rights ought to tell us something. Our Founders saw it. Without a Second Amendment, we wouldn’t long have a First.

John Zmirak is a senior editor at The Stream and author or co-author of ten books, including The Politically Incorrect Guide to Immigration and The Politically Incorrect Guide to Catholicism. He is co-author with Jason Jones of “God, Guns, & the Government.”