Why You Shouldn’t Panic About ‘Spikes’ and ‘Surges’ in New Coronavirus Cases

With the waning of the mass protests and riots, lauded by the press and politicians, the media were bound to turn their attention back to the coronavirus. One minute they are praising the protesters, the next they’re warning of the dangers of attending a Trump rally.

Nevertheless, cases did rise after lockdowns eased. A rise in cases sounds bad; at least, the press is doing its level worst to make it sound bad, and to frighten governors of states such as Texas and Florida, who have been saner than average.

But why should this panic us? A case (manifest illness needing or having official treatment) or an infection (just catching the bug, and no treatment needed or sought), are not as bad as a death from the bug. And there is no “spike” or “surge” in deaths.

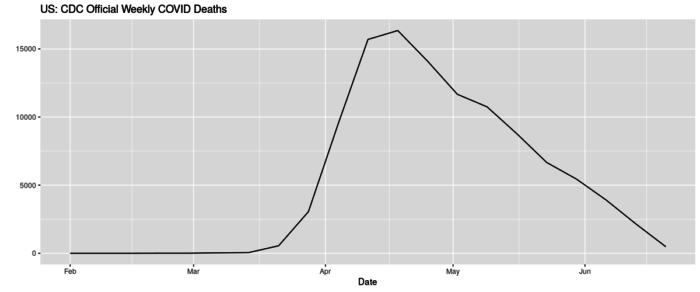

Here is a picture of the CDC’s official weekly COVID-19 deaths, current as of 26 June (the latest numbers available):

It’s important to distinguish between the official CDC deaths and media-reported deaths, which have been consistently higher by about 10% (see the Atlantic’s COVID-19 Tracking Project). As of June 26, the CDC ascribed 109,188 deaths to coronavirus, while the media reported 118,031, almost 9,000 higher.

The crisis, at least with respect to deaths, appears to be over.

The CDC’s numbers are also likely too high, with some deaths with coronavirus being labeled of, or caused by, coronavirus. Nobody knows the extent of this overstatement, which might take years to sort out.

Look at All-Cause Death Reports

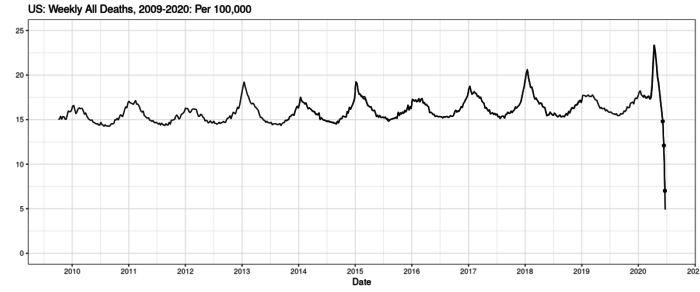

What we can do instead is look at the all-cause death reports. These are the weekly counts of deaths from any cause, normalized by population, from 2009 until late June (the CDC has two official sources, which have minor differences; both are plotted here).

The spike caused by coronvirus and seasonal flu are obvious, but then so is the drop off in deaths at the end. The drop off is not as dramatic as it seems, because it takes, according to the CDC, up to eight weeks to gather all reports, though after about two weeks the counts are usually more-or-less complete. The last three weeks are indicated with black dots.

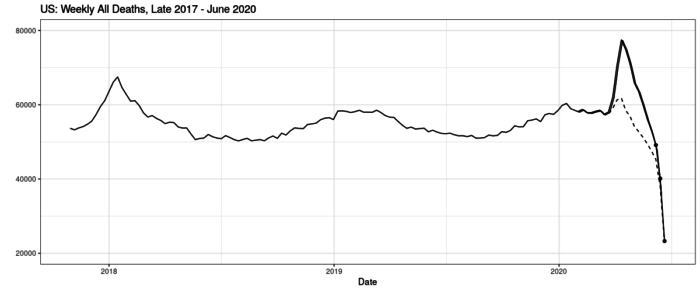

Since this graph is hard to read, here is a blow up, showing the actual counts (not per capita):

The solid line are the all-cause deaths, whereas the dashed line are the same subtracting official COVID deaths. Again, these numbers are subject to revision. But it’s clear, even with delays in reporting, that the count of deaths have dropped to usual seasonal levels.

The crisis, at least with respect to deaths, appears to be over. True, deaths might surge again at some future date, but that’s a trivial logical truth. Deaths might also drop if people start eating better, and that’s another logical truth.

On The Case

If deaths are dropping, how are “cases” rising? The coronavirus is probably still spreading somewhat. But most “new” cases are revealed because of testing. When people were locked down, many avoided going to the doctor and hospital for non-COVID ailments. After the lockdowns eased, they returned to have their bunions checked, were given routine covoronavirus tests, and were found either to have an active or past infection. If positive (active or past), they were officially recorded. Hence the “surge” and “spike.”

The media, incidentally, is nowhere close to distinguishing between new and old cases and infections. They report all tests as if they are new and serious.

Testing is also ramping up by official policy. For instance, the media trumpeted that Oklahoma recorded its “highest single-day increase” in cases. But they forgot to report that the state advertised free testing for that day, which led to higher than normal testing rates.

The media, incidentally, is nowhere close to distinguishing between new and old cases and infections. They report all tests as if they are new and serious.

The U.S. is now testing about half a million people every day.

You can’t find what you don’t test for. Even using the media’s worst-case-scenario numbers, by June 27 there were 2,498,822 reported positive tests and 119,156 deaths. That’s a death rate of 4.7%. There is no way the virus is killing 4.7% of the people it infects.

What’s happening is that most infections and cases aren’t being measured. This is not in the least unusual. Most who have the bug never have treatment, and many don’t even know they have been infected.

One study by Penn State estimated about 9 million Americans had an infection by March. The CDC says the actual number of cases is at least ten times higher than reported.

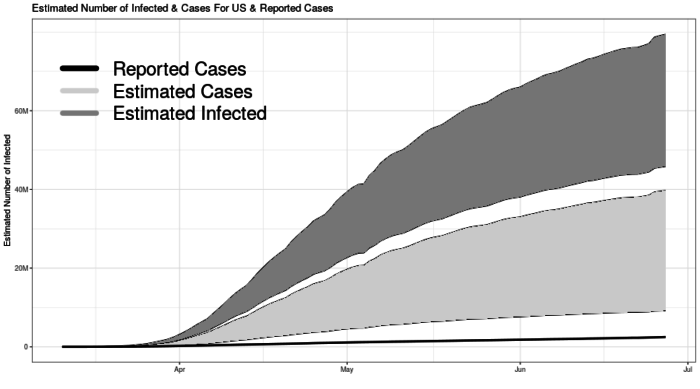

We can picture this using more careful estimates of infection and case rates collected by planned surveys of testing (rather than just looking at hospital reports; details are here). The estimated true rates give an idea of the true number of infected and true cases, defined as infections needing, but not necessarily receiving, official treatment.

The tiny solid line at the bottom are the reported number of cases, which is now about 2.5 million (as noted above). The true number of cases is, however, anywhere from 10 to 40 million. The true number of infections is 45 to 80 million.

Increased testing is revealing some of these previously unmeasured infections and cases.

They Won’t Let The Fat Lady Sing

These numbers suggest we are inching closer to herd immunity, the point at which spreading the disease to new people becomes much harder. The continued fall in both official COVID-19 and all-cause deaths, also suggest we should be less worried, not more.

Surely the press and government officials are bright enough to grasp these same statistics. So, why do they insist that the crisis is growing worse? I’ll let you answer that for yourself.

William M. Briggs is a senior contributor to The Stream, author of Uncertainty, blogger at wmbriggs.com, philosopher and itinerant scientist. He earned his Ph.D. from Cornell University in statistics. He studies the philosophy of science, the use and misuses of uncertainty, the corruption of science, and the uselessness of most predictions.