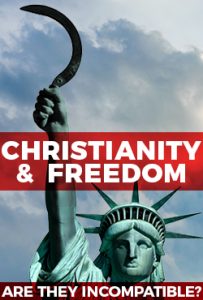

American Freedom was Founded on Knowledge of Man’s Fallenness

This essay is part of a series examining how American religious, economic, and political freedom are compatible with Christian views of a good society. It was provoked by the publication of the Tradinista Manifesto, which called for “Christian socialism” and an established national Church.

In the day of our nation’s birth the idea of self- government was so new as to be staggering. All of the great nations of Europe had been ruled by monarchs since time immemorial. For many the idea of detaching from something that had been stable and continuous for many centuries seemed like uncharted lunacy. It was a decidedly radical notion, if not a preposterous one.

What did it mean to say that this thing called “freedom” could coexist with government? How could this group at the end of the eighteenth century suppose they would accomplish this? Precisely how would their freedom be different from mere anarchy? And even if such freedom could somehow be achieved within the context of a government, how could it possibly be sustained? Wouldn’t anything like real freedom be tremendously fragile and therefore short- lived?

American freedom is, of course, nothing like pure and unmitigated freedom—which would indeed be anarchy and no freedom at all. True freedom must be an “ordered freedom,” at the center of which is what we call “self- government.” So to be clear: People would not have freedom from government, but would have freedom from tyrannous government, or from government that might easily become tyrannous. The ordered freedom given to us by the founders was meant to enable the people to govern themselves. But again, what made the framers think they could buck a trend extending back into the swamps of prehistory? How did they think they could create something so categorically different from anything that had ever existed?

The Two Secret Ingredients of American Freedom

The founders understood that for people to govern themselves, two things that had never before existed must be brought into existence simultaneously. Both spoke to an understanding of mankind that was corroborated by observation and history and that was, in the founders’ estimation, a biblical understanding of things. Each of the two things answered a particular question and solved a particular problem: The first understood that man was fallen, and the second understood that he could be redeemed.

The first of the two things was simply the structure of the government. A view of mankind as fallen meant that a government must be created that took this into account and whose very structure limited the power of any one part, lest that power grow and take over, devolving into tyranny. It was an observable fact of history that everyone wanted power and more power. If people had no power they wanted to get it, and if someone had power he wanted to keep it — and if possible to get more of it. So the founders must create a government that somehow took this into account, that was structured so that this fallen and selfish human desire for power actually worked against itself.

Checks and Balances Use Original Sin Against Itself

Of course, most of us know this as the ideas of democracy and checks and balances. The founders came to the idea of checks and balances mainly through the writings of John Locke and Montesquieu, and to the idea of democracy through the ancient Greeks and Romans. But who would believe that the citizens of those ancient societies were truly free? Rome was more an oligarchy than a true democracy, and it was a brutal society where being out of step with those in power could bring swift and cruel death. And Greece was the place where Socrates had been forced to drink a cup of poison for openly questioning the gods and ideas of that culture. If one’s thoughts were regulated by the power of the state, how could one really be free?

The founders would take the best of these ideas and improve upon them in some revolutionary ways to create the freest country that had ever existed — and more than that, the freest people. But again, what did they propose that was different from what had gone before? How could they safely give citizens a far greater freedom than anyone had ever enjoyed? Their success lay mainly in the second thing, which was unprecedented.

Freedom is Unsustainable Without the Virtues that Spring from Faith

This second piece was the secret ingredient, really, because it was not something that could be created in the way that a system of government could be created. It was infinitely more difficult than drafting a system of checks and balances. No, this second thing must already exist. And this second thing was the answer to the question of questions: What would enable a group of people to be trusted to govern themselves and then actually to do so?

“Religion” as the founders understood it was dramatically different from religion as it had been understood in other societies; in fact, we may well prefer the term “free religion” to simple “religion.” Because in America the idea of religious freedom was paramount.

Because one had to ask: If you enabled people to pick their own leaders, what would prevent them simply from voting for their friends, or for those who would favor them over others? Why wouldn’t they simply vote to line their own pockets or choose leaders who would give them what they wanted at the expense of what was right for everyone? Why wouldn’t they use this system to steal from the national treasury? In short, given the lesson of history that human beings were selfish and desirous of power, why should the founders assume that true self- government could ever work? The answer, as we have said, lies in the second thing. And that thing was, in a word, religion.

“Religion” as the founders understood it was dramatically different from religion as it had been understood in other societies; in fact, we may well prefer the term “free religion” to simple “religion.” Because in America the idea of religious freedom was paramount. It was always understood that one’s religion was truly free, which is to say not coerced nor mandatory nor affiliated with the power of the state in any way. This was also unprecedented.

The idea that religion was valuable in keeping people from misbehaving was not lost on rulers throughout history. Some rulers were tyrants who merely used state power to crush dissent and misbehavior and lawlessness, but other rulers cannily and often cynically understood that religion could help them to rule. They knew that religious people were less likely to misbehave. But the people were never free to believe as they liked. They were forced to go to church and bow to the ecclesiastical authorities just as they were forced to pay taxes or tribute and bow to the king. They did not have freedom of religion. There was one state church and the people must attend it and bow to its authority just as they bowed to the authority of the state. Indeed, the authority of the church and the authority of the state were in many situations precisely the same authority. Religion had been used to oppress people just as state authority had been used to oppress people. In the nineteenth century Karl Marx famously called religion “the opiate of the masses,” and regarding this kind of religion there is in fact great truth to his statement.

Religious Tolerance is Crucial Both to Faith and Freedom

The founders, however, had quite another idea, based on their experience in the colonies over the decades before, where the idea of religious freedom had become a central and vitally important issue. In fact, many had already experienced this religious freedom as part of normal life in the American colonies. Some of the very first settlers on American shores had left their lives behind precisely for this freedom. So the founders had observed something entirely different in America, something that had already operated in some places for nearly a century: a complete tolerance of all denominations and religions, such that the people were not coerced to believe but could believe and worship precisely as they wished.

They knew that the religion that was necessary to self- government was not coerced but free. True religion must be free religion. This was something new, and this was what made possible the unprecedented experiment in liberty that came to be known as the United States of America.

So the founders understood that freedom and religion went hand in hand, that freedom must have religion and religion must have freedom. One without the other was in fact neither. Freedom without religion would devolve into license or end in tyranny; and religion without freedom would really be only another expression of tyranny.

This column is adapted with permission from the author’s newest book, If You Can Keep It.