New Report Shows Why Foster Care Often Leads to Sex Trafficking

“Being in foster care was the perfect training for commercial sexual exploitation,” said a youth rescued from that abuse. Quoted in a report from the California Child Welfare Council, the child explained:

I was used to being moved without warning, without any say, not knowing where I was going or whether I was allowed to pack my clothes. After years in foster care, I didn’t think anyone would want to take care of me unless they were paid. So, when my pimp expected me to make money to support “the family,’” it made sense to me.

Placement in foster care can be one traumatic experience in a child’s life. Too often it comes before another one: commercial sexual exploitation. It can even contribute to it. But this can change. New legislation should support families and improve the foster care system in ways that will keep children away from sexual exploiters.

It Can Contribute

That’s the argument made by clinical social worker Christian O’Neill. He specializes in family support and stabilization. The paper, published last month, is titled “From Foster Care to Trafficking.”

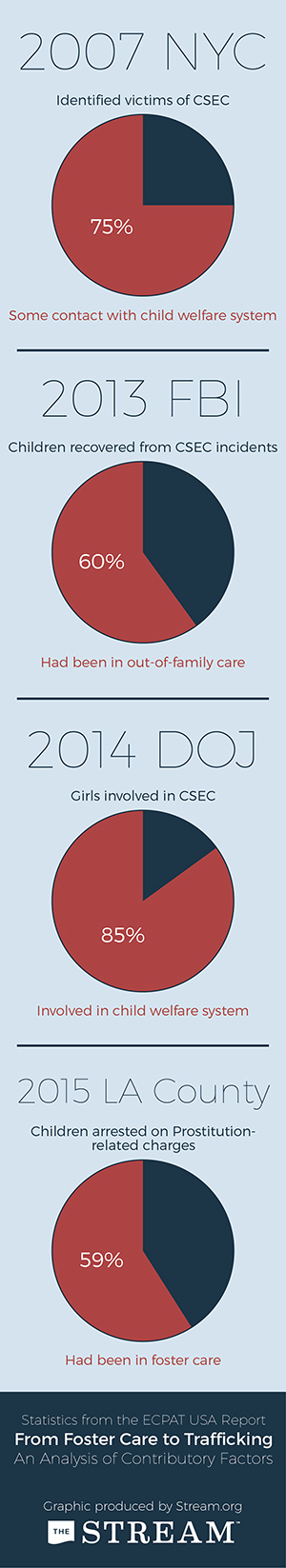

A large percentage of minors who survived the commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) have experience with the child welfare system, particularly foster care. O’Neill supports this with a slew of statistics, including these three:

A large percentage of minors who survived the commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) have experience with the child welfare system, particularly foster care. O’Neill supports this with a slew of statistics, including these three:

- “The FBI reported in 2013 that 60% of children recovered from CSEC incidents had previously been in out-of-family care.”

- “In 2015, California Attorney General Kamala Harris reported that 59% of children arrested on prostitution-related charges in Los Angeles County had previously been in foster care.”

- “A 2014 Department of Justice report estimated that 85% of girls involved in CSEC were previously involved in the child welfare system.”

While other researchers have noticed this connection, he says, no one has given a persuasive answer to why it happens.

Why Would Services Designed to Help Children End Up Hurting Them?

Here are nine key points from O’Neill’s paper that help explain why foster care often leads to trafficking. The basic reason: The instability of foster care makes them vulnerable to exploitation.

- Placement in a foster home is inherently traumatizing. Children may lose their connections to their family. They also lose their connection to the places and people they are familiar with, like their school, friends, and teachers.

- Foster parents are paid by the government. Children in foster care are often all-too aware that their presence brings their foster parent a government paycheck. They can feel their caregivers have them just for the money.

- Many foster children are frequently uprooted and moved around. Children often feel that they are moved from home to home arbitrarily, and without warning.

- Families are torn apart unnecessarily. 78% of children who CPS deemed victims in 2012 suffered only neglect at home, without physical, sexual or psychological abuse. Many neglect cases are largely due to poverty. Instead of being split up, many of these families could have been better helped by family preservation services. These include training in budgeting and nutrition.

- Federal funding currently favors foster care. Until a new law goes into effect, federal funding for foster care is considered a non-discretionary entitlement, i.e. unlimited. On the other hand, funding for family preservation services is limited and accounts for only five percent of federal spending on child welfare.

- Foster care homes can be abusive. Because so many families are torn apart unnecessarily, more children need placement than there are foster families. This results in lower enforcement of foster home vetting standards and reduced foster home quality, as well as placement in group homes. All can harm the children.

- Traffickers know foster kids are vulnerable targets. Traffickers frequently recruit near places likely to be attended by foster children. They know foster children are more likely to be traumatized and susceptible to their messages. O’Neill suggested that lack of adequate supervision, awareness and training of personnel to combat this targeted recruitment may be another significant risk factor.

- Foster children frequently run away. They can feel the streets offer more control than their foster care provides. There, a trafficker offering attention and care can easily pick them up. Once they run away, they are unlikely to receive follow-up investigation.

- Aging out of foster care can leave a foster child stranded. Once minors age out of foster care, they are likely to become homeless and be left without a significant family connection to return to for support.

Our nation’s system creates a story that leads to commercial sexual exploitation for many minors. This story will continue if we don’t recognize what’s happening and create change.

An Overhaul is Coming to American Child Welfare Services

Change is on the horizon. A new federal law rolling out in 2019 will prove “the most extensive overhaul of foster care in nearly four decades.” That’s according to Pew Charitable Trusts, a public policy think tank. This law, called the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), was part of the spending bill signed by President Donald Trump in February. The law changes the way child welfare services are funded by the federal government.

It makes family the new priority. FFPCA majors on keeping families together by putting more money towards parenting classes, mental health counseling and substance abuse treatment. Also, it significantly limits funding for group homes. Now most group homes will only receive federal funding for a child to stay in a group home for two weeks, with a few exceptions.

The new act will “upend the system,” O’Neill says. It “finally” begins to prioritize preventative service programs for families over placement in new homes. However, he notes that states can opt to delay its roll out for up to two years. Measuring the law’s impact will take even longer.

Former Foster Child Agrees

Tasha Benz agrees. A 25-year-old Oklahoma native, she works as a “house mom,” or child-care worker. She works at a shelter for minor girls who are recovering from commercial sexual exploitation. She agrees because she knows something from personal experience. Her sister spent years in foster care before being exploited by a sex trafficker. Thankfully, her sister escaped.

From her experience, she says, O’Neill is exactly right. She had to move a lot as a child in foster care, though she was never trafficked. Her sister, who was trafficked as a minor, moved frequently because of foster care. “She was took from facility, to facility, to group home, to group home.”

Benz said the parallel between is also clear. In sex trafficking, “your pimp … gets paid for what you do.” In foster care, “If it’s not a good experience, it feels like you were just bought,” she says. In her sister’s experience with foster care, “they didn’t care for them at all.”

Yet she pushes back on the new budget changes. Her personal experience with foster care was positive. But her brief experience with one good specialized community home is not like the experiences of many who are trapped in multiple uncaring foster homes for years. As far as preventative programs, Benz said their effectiveness will be limited to the willingness of parents to participate in them.

Benz saws the way foster care hurt her sister and made her vulnerable to sex traffickers. But she pointed out some parents may be unwilling or unable to be good parents. For some children, a small specialized group home like hers, and foster care in general, can provide a positive experience.

‘Still Far More Work to be Done’

O’Neill acknowledges the new law’s potential for good. But he also described a need for awareness and action on a broader level. “There is still far more work to be done,” he said. “Everyone, regardless of their position or rank within the human services field, has a vital role to play” in protecting children from trafficking and sexual exploitation.

O’Neill’s conclusion is direct and hopeful. “We need to develop a common, federal-level vision for keeping children in their homes and out of foster care,” he writes. “Instead of complying with a system that retraumatizes children and places a dollar value on their heads, we can work collectively to create one that nurtures, protects, and empowers them, and in doing so set a bold example for the rest of the world.”

Foster care is one solution to less-than-ideal family situations. Many loving people do the important work of fostering and adopting. But it’s a risky solution, especially as the foster care system is now designed. According to this report and others like it, in many cases the system of foster care can prove traumatic, impersonal, and steal permanence and family from a child. The government is a poor substitute for healthy family.