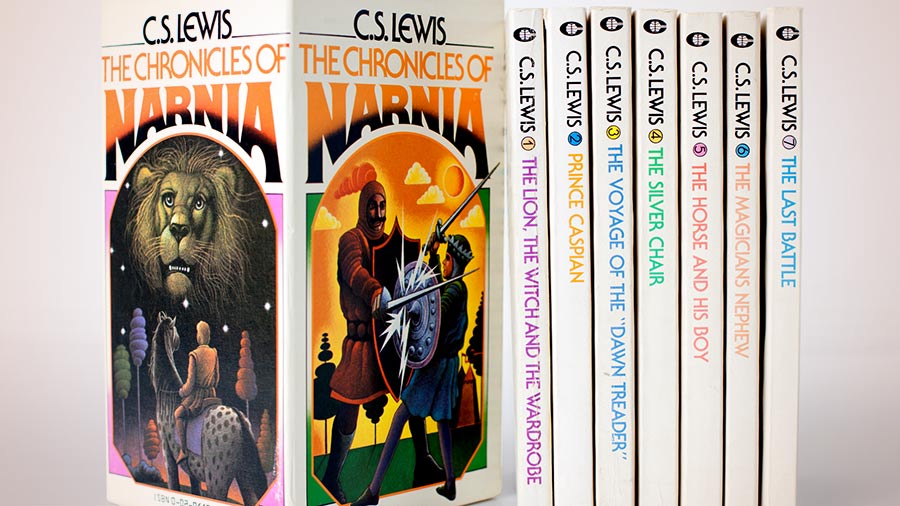

Did Susan Pevensie (From The Chronicles of Narnia) Go to Hell?

‘What wonderful memories you have! Fancy your still thinking about all those funny games we used to play when we were children!”

So Susan Pevensie tells her cousin Eustace Scrubb in the final volume of C.S. Lewis’ classic children’s series, The Chronicles of Narnia. Susan no longer believes in the land of Narnia or the great lion Aslan, whom she once watched die and rise from the dead. She is more interested now in “nylons and lipstick and invitations,” as another “friend of Narnia” notes with disgust.

It’s Time to Grow Out of Narnia?

Some people agree with Susan that we should grow out of Narnia, and even the Kingdom of Heaven of which Jesus of Nazareth, who also died and rose again, often spoke. Isn’t it time to put away such childish notions? And why did Jack Lewis damn poor Susan to hell?

J.K. Rowling summed up Susan’s fate as follows: “There comes a point where Susan, who was the older girl, is lost to Narnia because she becomes interested in lipstick. She’s become irreligious basically because she found sex. I have a big problem with that.”

Philip Pullman, author of The Golden Compass, had a problem not only with Susan being “left behind,” but with the Christian take on life, death, and judgment, as he understood it, including in the Narnia stories. “One of the most vile moments in the whole of children’s literature,” he said, comes when Aslan informs the children that they have died. Lewis “solves a narrative problem” by “slaughtering the lot” of his characters, then says they’re better off dead! Pullman described this as “propaganda in the service of a life-hating ideology,” and “par for the course” for Lewis, for whom “Death is better than life; boys are better than girls; light-colored people are better than dark-colored people; and so on.”

Narnia is full of such “nauseating drivel,” said Pullman, and Susan’s fate is typical:

Susan, like Cinderella, is undergoing a transition from one phase of her life to another. Lewis didn’t approve of that. He didn’t like women in general, or sexuality at all, at least at the stage in his life when he wrote the Narnia books. He was frightened and appalled at the notion of wanting to grow up.

Was Susan Really a Lost Soul?

Now all this is remarkable nonsense for so talented a writer. The author of Allegory of Love hated sex? A lively and generous correspondent with many of the wittiest women of his time had it in for females? A man who served his country in war, tutored and taught, wrote brilliantly, aided the poor, took care of drunken relatives, and opened his home to war refugees, never grew up?

But even Lewis’ fans wrote him concerned letters about poor Susan. Was she really a lost soul? Why did Lewis object to the natural process of growing up and dating? On parallel lines, some now ask why the Religious Right wants to “punish Americans for having sex?”

In fact, Lewis was not shy about love, but these stories were written for younger children than His Dark Materials or even Harry Potter. And frankly, there is something creepy and arguably “vile” in the way Pullman sexualizes twelve-year-olds in his tales.

As for the claim that Lewis hated life, in fact, his writings resoundingly echo God’s verdict “It is good” upon Creation. In 1955, about when he was writing The Last Battle, Lewis sent a letter to Mary Van Deusen that reveals what a sunlight-hating underworld gnome he truly was:

I am so glad that you are finding (as I do too) that life, far from getting dull and empty as one grows older, opens out. It is like being in a house where one keeps on discovering new rooms.

But death is a part of life, Forrest. Lewis often wished that it wasn’t — read his accounts of the deaths of loved ones, beginning with his mother, and ending with the searing notebooks after his wife’s passing, and tell me Lewis was blase about life or death. Literature, I often told my students, is about everything. Since Lewis believed in life after death, why shouldn’t he try to depict it?

Rowling and Pullman completely misread the story of Susan. In fact, Susan’s story is not of damnation, but temptation. She is the original “material girl.” She has become a queen in the old-fashioned sense: not like early European queens who were praised for bettering the lives of her subjects, but addicted to vanity. Her problem wasn’t sex or growing up: she had beaus in Narnia. And her “judgment” was not hell, it was that she missed (for now) what she purposely rejected: she was granted the grownup right to avoid a party she didn’t wish to attend!

This is the nature of temptation and choice that Lewis describes so well, and which, for all our chatter about “a woman’s choice,” we have become too infantile to face. Being an adult means making tough decisions. Roads diverge, and fork in different directions. True feminism, or adult masculinity, means recognizing the consequences of our decisions. So in The Last Battle, some talking animals look at Aslan, hate him, and enter the shadow willingly. They reject the gifts Aslan gives, such as reason and love. They limit themselves (at least for the time being) by their choices.

Susan, the Anti-Feminist

Susan’s problem, Polly explains, is that she has not grown up enough. “Her idea is to race forward to the most foolish time of life, then stay there as long as one can.” No boys are mentioned, just nylon, lipstick, and “invitations” (dates). Susan’s actual fault was that of a pious woman Jesus met: she wasn’t enough of a feminist!

“Blessed is the womb that bore you, and the breasts that gave you milk!”

“Blessed rather are those who hear the Word of God and obey it.”

In most ancient civilizations, women were largely confined to the roles of consort and mother, that is, to reproduction. (Plus knitting and house management.)

Miracles, I argue, make us more human. Among Jesus’ greatest miracles was that he made the world see women as full human beings. (Even those who reduced themselves to breast, womb, or broom.) Matching, mating, and mothering had to come first in the ancient world, with its high infant mortality. But life is more than bread, or the energy that Pullman calls dust, and the Chinese call qi. Life originates in the deepest magic of all, self-sacrificial love. Susan painted herself into a corner: the hell of reductionism into which the sensual hedonism of technology is also now reducing the young.

Please Support The Stream: Equipping Christians to Think Clearly About the Political, Economic, and Moral Issues of Our Day.

The Romans scattered body parts across their empire. We have become their disciples by reducing human reproduction and parenting to mere sex, then aborting the products of conception.

In Sex Matters, Mona Charen notes that drunkenness has increased, and female happiness decreased, even as sexual “freedoms” expand. “Romance and love, two of life’s greatest joys, must begin with interest in the whole person,” she argues. Lipstick and nylon are not “the whole person.” Damnation, Lewis saw, means being imprisoned within ourselves. If lipstick can free us of the self — by using it to paint beauty, delight a lover, or dress up as a clown and make children laugh — then truck cases of the stuff to Susan’s front door. In fact, when Jill Flewett, who stayed at the Lewis home outside Oxford during the war (some say she was the model for Lucy), wished to act, Lewis helped pay for the training that launched her successful career! No doubt she wore lipstick and nylons on stage.

Confucius defined himself as a man so curious that he didn’t notice the passage of time. Susan risked becoming a princess, a Mrs. Haversham, rather than a self-forgetful lover, mother, scientist, musician, grandmother, and follower of Christ — until a fateful BritRail train went off the tracks.

As often happens in adolescence, “growing up” narrowed Susan’s world. Edmund was tempted by greed, Eustace by social nihilism, Mark Studdock by the lure of the “inner ring,” Frodo by a golden ring. As the singer Mark Heard put it, “You’re not in love, not even with your lovers.” For a while, Susan neglected not only her “first love,” but all “I-Thou” relationships.

Get The Stream’s daily news roundup, quick and served with a healthy splash of humor. Subscribe to The Brew

Susan was not yet a witch or balrog, though. Her character was still in flux. Lewis told Pauline Bannister in a letter, “I have a feeling that the story of her journey would be longer and more like a grownup novel than I wanted to write,” suggesting that Pauline write it herself.

Yet Susan’s fate does sound a warning. Boromir was seduced by the ring but repented and died a good death. No hero in Harry Potter fell so low: in that sense, Rowling’s fantasy was less true to life or “grown up” than that of Lewis, Tolkien, or the Brothers Grimm.

The Shoddy Lands

One of Lewis’ lesser-known short stories shows that in the tale of Susan, he was also warning himself.

A former student (his story goes) comes to visit Lewis with his fiancé. During the visit, Lewis nods off, and finds himself strolling through the girl’s subconscious. Most objects in that land seem dreary: trees are vague blurs, most flowers are smudges, people look indistinct. But here and there something stands out: fashionable women’s clothing, the faces of certain men. The girl’s own figure rises like a giantess preening in front of a mirror. Two sounds are barely audible: her boyfriend knocking to be let into her world, and the deeper, quieter call of Christ.

Waking, Lewis felt sorry for the boyfriend, but also worried lest anyone tour his psyche and witness the idols that he has set up.

“Then we shall know, even as we are known.” Beginning in a sense with Augustine’s Confessions, tearing off masks and revealing our true faces has been the job of the novelist since Christ came into this world. For this reason, Susan is one of the most important characters in the Chronicles of Narnia.

Epilogue: In The Case for Aslan: Evidence for Jesus in the Land of Narnia, I take Lewis at his word, and tell how an adult Susan, having lost her family in that train accident, begins to seek Aslan “by another name” in this world. It is, indeed, a “more adult” story, as Professor Digory Kirke helps Susan navigate through critical scholarship on the historical Jesus, over a scone at an old pub in Oxford.

David Marshall holds an undergraduate degree in the Russian and Chinese languages and Marxism, a masters degree in Chinese religions, and a doctoral degree in Christian thought and Chinese tradition. His most recent book is Jesus is No Myth: The Fingerprints of God on the Gospels.