Rediscovering the Divine Vision of George Lucas

Dusting off (quite literally) the original Star Wars trilogy and the VCR needed to play them, I settled in for a heaping holiday helping of childhood nostalgia. But there’s more than just child’s play at work in the vision of George Lucas. He imagined an incredible universe and created the industrial light and magic needed to make it come alive but used all that to make a cinematic case for the power of religion and the value of maintaining close contact to creation.

Not surprisingly, my VHS prep was a refresher before venturing into the theater for Episode 7. Thankfully, The Force Awakens never ends up in a ditch like The Phantom Menace, the first prequel piloted by the infamous Jar Jar Binks. Instead, it’s a satisfying (at least in the short term) trip down memory lane for us old-timers and probably more than enough to hook a new generation of pre-teens. And (spoiler alert) it seems the next generation is being primed to travel the same path that we did in the 1980s.

The latest film is largely a “but this time” remake of the first Star Wars. Both movies center on a spunky orphan full of adolescent angst marooned in a desert landscape, but this time it’s a girl. Ditto on an endearing droid with an important map, but this time it’s orange and rolls. An alien cantina filled with fantastic life-forms where one can find a ship to take you where you need to go? Check. But this time it’s owned by a tough but motherly Amelia Earhart figure.

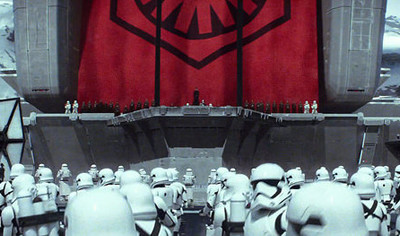

There are again Nazi types with a huge weapon that can obliterate planets, but this time it’s even bigger. There is also a Jedi and a masked pupil gone bad, but this time Luke Skywalker is in the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi. An independent minded rebel on the run who must decide if he cares only for himself or will help the sassy lass who has caught his eye? Yep, but this time he’s black and a reformed storm trooper. And on and on.

Faith and the Force

Since J.J. Abrams seems intent on a retro ride rather than a major plot twist, let us turn our attention back to Lucas and the originals. Unlike C.S. Lewis’s Narnia with its clearly identifiable Christ character Aslan or J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings which is less allegorical but still very Christian in its imagery, Lucas created a world where the faiths of East and West mix and mingle. Perhaps, this is what one should expect from a child raised in an observant Methodist home but who was intrigued by the liturgy of Lutherans and Catholics and explored Buddhism as a young adult. Lucas would go on to count noted mythologist Joseph Campbell as a mentor and has said much of his work is rooted in a question he asked his mother as a young boy: “If there is only one God, why are there so many religions?” He’s been “pondering that question ever since.”

The religious meaning of Star Wars is prime debate fodder for fans and even the basis for a not-joking Jedi Church or two. The Force is probably more yin/yang than Holy Spirit, but a Christian pastor looking for a sermon hook could certainly tie in Paul’s sweeping introduction to Colossians where Jesus is described as “before all things, and in [whom] all things hold together.” Additionally, Luke Skywalker’s decision to put down his light saber and attempt to redeem Darth Vader through loving sacrifice rather than destroy him via violence certainly has echoes of Gethsemane and Calvary. Still, those of us who both bow to Christ as savior and appreciate Star Wars should not try to cram the film’s spirituality into an exclusively Christian box. It just won’t fit.

Lucas simply does not have the theological clarity of a Lewis or Tolkien, but the message of Star Wars can still serve as a useful cultural bridge to theism, and that was very much by design. “I’m telling an old myth in a new way,” Lucas explained to Bill Moyers in 1999. He “didn’t want to invent a new religion” or displace the Bible and other religious texts but instead saw “the whole point” as creating “a tool that can be used to make old stories be new and relate to younger people.” Worried that the culture was losing its moorings, the self-described “son of a small-town businessman” who into the 1990s characterized himself as “very conservative, always have been” wanted to get people thinking and asking questions about the divine, as well as themes like friendship and loyalty. The brain behind Star Wars once summarized his goal this way:

Knowing that the film was made for a young audience, I was trying to say, in a simple way, that there is a God, and that there is both a good side and a bad side. You have a choice between them, but the world works better if you’re on the good side.

There could certainly be worse messages embedded in a mass media phenomenon.

Nature Loving Sci-fi

My adult eyes also detected a consistent critique of technology and embrace of the organic that I missed in my youth. You may remember that the always out-gunned Rebellion only succeeds in Star Wars because Luke Skywalker turns off his targeting computer and takes aim at the Death Star through the eyes of faith. The theme continues in The Empire Strikes Back as Luke journeys to the decidedly low-tech but verdant home of the simple living and diminutive master Yoda to continue his training. And in the trilogy’s final act, Return of the Jedi, the aboriginal Ewoks and their Stone Age tools prove crucial to defeating the high-tech forces of darkness.

Yet, the message is not a simplistic “nature good, technology bad.” Throughout the trilogy, droids, especially the child-like R2-D2, act heroically. Technology, for Lucas, can be a force for good as well as evil. In Empire, Yoda uses his spiritual strength to raise young Skywalker’s spaceship from the bog, demonstrating the great power of faith. Yet, while the Force is strong, a Jedi doesn’t just fly around the galaxy like Superman, one still needs an X-wing fighter for that. In Jedi, despite an initial surge when the Ewok warriors bravely join the fray with their spears, the storm troopers and their laser blasters soon regain control and all again seems lost. The final turning point comes when Chewbacca and two Ewoks capture an Imperial forest walker, turning its powerful guns on the Empire’s forces.

Interestingly, Chewbacca is a character too often dismissed as a mere side-kick who provides occasional comic relief, but look close and you can see a lot of Lucas in him. The two certainly share a fondness for big hair and they can get overlooked when it comes time to bestow the big awards. (Lucas never won an Oscar, and in Star Wars Chewie famously got snubbed when they handed out the medals.) Both seem a bit out of place socially among humans.

George and Chewie speak in public infrequently and somewhat clumsily. For the 1995 trilogy video release, Lucas sat down with fawning film critic Leonard Maltin for an awkward interview that nevertheless produced a few nuggets. Lucas noted that he purposely put his heroes in earth tones while the Empire is a colorless grayscale world. He described Wookies as “earth people,” and you could probably describe Lucas as an “earth person” too. After the success of Star Wars gave him the ability to live and work wherever he wanted, Lucas chose to take root away from Los Angeles, creating Skywalker Ranch on a stunning spread in northern California. With encouragement from Lucas, Bill Moyers would come there to film Joseph Campbell and The Power of Myth became a smash hit, at least by PBS standards.

Following Darth Vader and C.S. Lewis?

Lucas, who early in his career spoke with disdain about the ways of Hollywood, was able to grab control over a powerful part of its machinery. He initially tried, like Chewbacca, to use that for the cause of good as he saw it. Today, many would argue that his efforts were co-opted and that he became, a bit like Darth Vader, more machine than man as he zealously guarded the Star Wars marketing empire. Lucas also largely forgot how to tell his core story for the prequel Episodes I, II, and III — getting lost as he excitedly played with the new CGI toys at his disposal.  He then sold off the Star Wars universe to Disney for $4 billion. Perhaps, though — again like Vader — Lucas will be redeemed in the end.

He then sold off the Star Wars universe to Disney for $4 billion. Perhaps, though — again like Vader — Lucas will be redeemed in the end.

The usually media-shy and tight lipped Lucas has openly professed a belief in God. Even if that deity is not exactly the God of the Bible — “all the religions,” he says, “are true, they just see a different part of the elephant” — this level of theistic faith is still a rarity in Hollywood. Lucas told biographer Dale Pollock decades ago that he thinks about what will happen when he dies, worrying that he will come face to face with God and hear, “You’ve had your chance and you blew it. Get out.”

I, for one, pray that he does not blow it but can follow the path of C.S. Lewis, another student of mythology who journeyed through theism before he came to know Christianity as “a myth which is also a fact.” Even if he does not, by creating the world of Star Wars, Lucas has at least helped to keep the Great Conversation alive for many, and that alone is no small accomplishment. George Lucas, may the Force (and the Lord) be with you.

John Murdock is a lawyer who writes from his native Texas and greatly enjoyed breaking out his old action figures this Christmas. His online outpost johnmurdock.org remains undetected by the Empire.