Netflix’s Messiah Reviewed: Who’s Your Messiah Now?

Warning: Spoilers ahead.

Editor’s note: This review contains spoilers.

“One man’s messiah is another man’s heretic.” That’s the opening line of my first book on Islamic messianic figures. It’s also an apt summary of Netflix’s excellent new show Messiah. Its 10-episode first season was released on Jan. 1. Let’s hope it gets renewed. We need to know how this story of a charismatic Middle Eastern miracle worker, who not only attracts Christians, Muslims and Jews but sways the U.S. President, plays out. Here’s a brief (as possible) summary.

A Modern-Day Messiah?

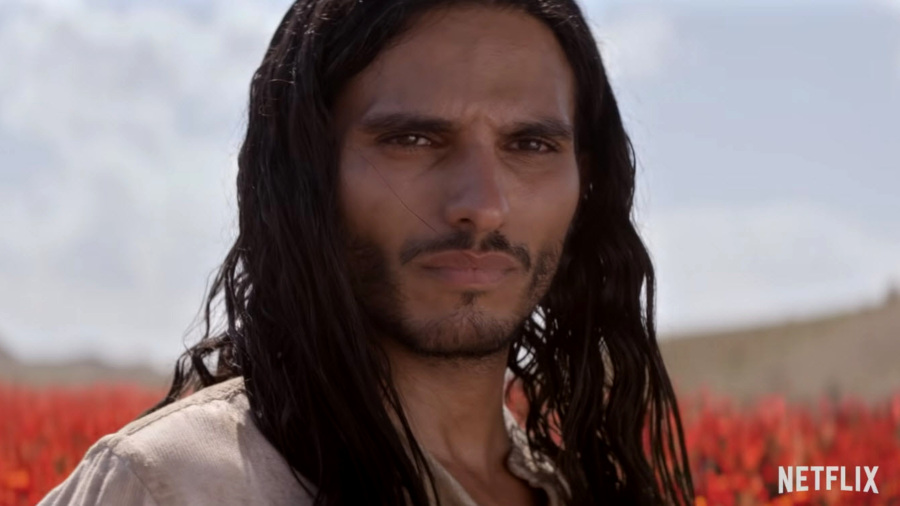

A long-haired, thinly bearded man appears in Damascus and accurately predicts the destruction of besieging ISIS forces. Many Palestinians there follow him into the desert, believing him to be al-Masih, “The Messiah.” He leads them to the Israeli border. The movement gets on the CIA’s radar screen. The group reaches the Israeli border, and al-Masih crosses. He’s arrested and interrogated by a Shin Bet agent, about whom he knows personal details. He then disappears from prison (later we find out the prison guard let him go, believing him the Messiah) and reappears on the Temple Mount. In a confrontation near the Dome of the Rock, Israeli soldiers shoot a young boy — whom al-Masih heals. He then disappears again, showing up soon after in Dilley, Texas. He is caught on cell phone cameras stopping a tornado about to destroy the Baptist church. This goes viral and many flock to the town. The church pastor believes him to be Jesus returned and becomes his spokesman and handler.

“One man’s messiah is another man’s heretic.”

The FBI arrests him for, ironically, entering the U.S. illegally. The lead CIA analyst comes to Texas and questions al-Masih. The FBI agent figures out he’s parroting ideas about “creating confusion” from a book by a former college professor and convicted terrorist. It turns out that al-Masih studied for one semester in the U.S. under this fellow. An immigration judges grants al-Masih asylum, despite the best, nefarious efforts of the White House Chief of Staff. The Shin Bet agent shows up in Dilley, intending to kill the alleged messiah — but cannot.

CIA learns that al-Masih is really an Iranian named Payam Gholshiri. The Baptist pastor, his family and hundreds of followers, along with al-Masih, leave Texas in a caravan. They eventually reach Washington, DC where their leader walks across the water of the Reflecting Pool. Back in the Middle East, most lose faith in al-Masih, except for a young man named Jibril. He, his friend Samir, and others are taken to a refuge in Jordan. There, a shaykh questions his beliefs, telling Jibril that his mentor is really al-Masih al-Dajjal — the Islamic antichrist. Another Muslim leader trains Samir and his friends as suicide bombers.

An Iraqi Refugee Trained in Illusion Who Works Miracles

A CIA operative finds Gholshiri’s brother in Tehran. He learns they were Iraqi refugees taught the art of illusion by their uncle. The agency also discovers he spent time in an Iranian psychiatric prison for a “Messiah complex.” Gholshiri is brought to meet the U.S. President and tells him world peace requires America withdraw all overseas forces. The President, a Mormon, almost believes, and considers it. Gholshiri and his followers are living in a hotel in D.C. When asked if he’s the Messiah, he tells CNN “I am here to bring about the world to come.” He also says that God “wants the Flood.”

The lead CIA analyst contacts Gholshiri’s former professor in Russia, who tells her that he serves al-Masih — not the other way around. Gholshiri is invited to speak at a mega-church in metro D.C., but instead goes willingly with Israeli agents to be rendered back. In his stead the Dilley Baptist pastor’s daughter speaks of her faith in him, before collapsing in an epileptic fit. Similarly, in the main mosque in Ramallah, Jibril professes his faith in al-Masih before a suicide bomber enters. It’s his friend Samir, who at the last moment drops the detonator — only to have his handler set off his vest remotely. Many die but Jibril survives, wounded.

The plane heading back to Israel crashes in North Africa after one of its engines explodes. A shepherd boy finds the site. He tells the Shin Bet officer that he, and the others, were dead until Gholshiri raised them. The final scene of the first season shows one of these resurrected Israelis kissing al-Masih’s hand, weeping.

Themes: Biblical and Quranic Quotations, the “End of History”

There are several prominent themes in Messiah. One is quoting passages from both the Bible and the Quran. In fact, five episodes’ titles are directly from the Bible, while one—“God Is Greater”—is the Muslim battle cry according to several hadiths. (These are alleged sayings of Islam’s founder Muhammad.) The Scriptures of both religions are also adduced several other times, by various characters. In the most notable example, Pastor Felix Iguero talks to al-Masih after his Texas church survived the tornado. Iguero quotes Revelation 1:7: “look he is coming with the clouds and every eye will see him, even those who pierced him. And all peoples on earth will mourn because of him. So shall it be! Amen.” To which al-Masih replies “I am the Alpha and the Omega” — appropriating the words of the returning Christ. All told, six Biblical and five Quranic passages are used in various episodes. But none of the latter are the ones that actually mention al-Masih (which are mostly found in Sura al-Ma’idah [V]). And in fact Jesus’ return is only hinted at in the Quran. But it’s described in detail in hadiths, a number of which contradict the story line in this show. (On which more, below.)

Another major motif is the “end of history.” Five times this concept is highlighted. Eva Geller, the CIA analyst, is shown in the opening episode discussing the idea and the famous 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations (by the late Samuel Huntington) with a college student in a late-night diner. That same student, later on, burns the book along with the paper he wrote on it, after al-Masih’s miracles. The main character himself speaks of history ending three times. He tells the people of Damascus, the crowd before the Dome of the Rock, and the U.S. President that such is happening.

But the end of history thesis is not Huntington’s. It’s from Francis Fukuyama’s 1992 The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington actually argued against history ending and Fukuyama’s post-Cold War optimism that democratic capitalism would win the future. He in fact predicted conflict rooted in religion would replace the ideological kind. So the writers’ choice of books to illustrate messianic ideals is curious, to say the least. Is this an attempt to smear Huntington, who is widely detested on the Left for allegedly “awakening a hatred for other civilizations?” It’s hard to tell.

Cultural Confusion

The third prominent concept is “cultural confusion.” The show’s namesake is believed initially, by CIA and FBI, to be motivated by this idea as espoused by his former college professor. What the writers seem to mean by this is a variant of “accelerationism.” This is a process that some radicals — both right and left — hope will radically alter society. It normally depends on rapid technological changes to do so. But as Geller tells the White House Chief of Staff in a briefing: “What better agent of chaos than a new messiah?” Especially one who does miracles.

The man who would be messiah performs six of these in the 10 episodes. He predicts/causes the defeat of ISIS. He knows intimate and past life details of people he meets. Gholshiri heals a boy of a bullet wound and stops a tornado. In the most Christ-like fashion, he walks on water and raises the dead. Yes, a master illusionist might be able to pull some of those off. But not all, and certainly not the last one. So who, and what, is this Gholshiri fellow?

Problems With the Show, Starting With the Small Ones

There are problems with this show — some minor, some more significant. Here are some of the former. CIA analysts don’t grab a gun and do field work, except on screen. Almost all the Christians in Messiah are Evangelicals. We do see one shot of a Vatican spokesman explaining that “Pope Alexander” is having al-Masih investigated, but that’s about it for non-Protestants — except for one Mormon (the President). One would think the Orthodox Christians in the Middle East might have an opinion on such a figure.

Similarly, the Islamic world seems to consist entirely of a strip from Damascus to Jerusalem, and then only of Sunnis. At one point Geller is reading documents from Tehran University pertaining to Gholshiri — but they’re in Arabic, not Farsi. Some of the subtitles rendering spoken or written Arabic are dicey, at best. For example, kafir means “infidel” or “unbeliever” — not “heretic, as it’s translated. And my favorite: no one in any vehicle ever wears a seat belt.

Messiah’s Alleged Messiah Falls Short in Both Christianity and Islam

More damaging to the show is its misunderstanding, or misrepresentation, of Islamic eschatology. The main End of Times figure for Islam is the Mahdi, the “divinely-guided one.” This is whom Allah will send to take over the world for Islam. (Both Sunni and Twelver Shi`is believe in him. The difference is that for the former, he’s not been here yet. For the latter, he was the 12th Imam after Muhammad, disappeared in the 9th century AD, and will return.)

The Messiah in Islam is `Isa bin Maryam, “Jesus the son of Mary.” But the Mahdi outranks Jesus. In fact, the Mahdi will appear on earth first, gain followers, and go into battle against al-Masih al-Dajjal, “the deceiving messiah” (or Antichrist). But he will be unable to kill him. Only then does Jesus return, by descending from heaven into either Damascus or Jerusalem (the hadith accounts vary). A number of other eschatological signs and figures will also have appeared by then, as well. One of the most notable is “the Sufyani,” a powerful and evil leader in Syria. The other is the collective Yajuj and Majuj (“Gog and Magog”), rapacious creatures from central Asia.

Messiah deals with none of this. Yes, it’s a show produced by, and primarily for, a Christian audience. But the central figure comes from the Middle East, and one of this two main groups of followers is Muslim. Gholshiri as al-Masih would not be believable as either the returned Jesus or the Mahdi. Maybe as the false messiah (which several individuals in fact call him). Messiah’s main figure is a more of a Messiah Lite, aiming to appeal to members of both the world’s two largest religions — but falling short of believability in either register.

How Would Political Leaders of Islamic Nations Respond to This Figure?

This helps explain why we see no sign of any Iranian or Turkish reaction to Gholshiri as al-Masih. Both countries’ leadership expect the Mahdi to come. (See the Constitution of the Islamic Republic, Article 5. And some in Turkish President Erdoğan’s inner circle are committed Mahdists — although it’s not wise to say so publicly.) And large numbers of Muslims around the world expect the coming of the Mahdi (42%) and Jesus (35%) “in their lifetime.” ISIS (and to a lesser degree al-Qaida) predicated their actions on “hotwiring the apocalypse” — forcing Allah to send the Mahdi.

A show purporting to deal with Middle Eastern messianism should give us some indication of how such claims are playing in two of the region’s major nations. The Iranians might have had him under psychiatric evaluation earlier in his life, as per the show. But miracles have a way of dispelling doubts, even for Twelver Shi`is. And while Erdoğan’s ego probably wouldn’t allow for a competing messianic complex, that doesn’t mean pious Turks wouldn’t follow one such. ISIS, on the other hand, would probably deem him the Antichrist, as the trainer of the suicide bombers does.

How Would You Respond to a Messianic Figure?

The final issue this show presents is not one of Islamic theology or geopolitics, however. It’s the question of how Christians would respond to such a figure. And in its limited way, Messiah confronts this head-on. What would YOU do, Christian reader, if a long-haired, soft-spoken, seemingly meek and mild man from the Middle East stopped a tornado, walked on water, and raised the dead? Yes, we know the warnings of Christ Himself. “Take heed that no one deceives you. For many will come in my name, saying ‘I am the Christ,’ and will deceive many” (Matthew 24:4,5).” Also “Then if anyone says to you, ‘Look, here is the Christ!’ or ‘There!’ Do not believe it. For false christs and false prophets will rise and show great signs and wonders to deceive, if possible, even the elect. See, I have told you beforehand” (Matthew 24:23-25). As the Orthodox Study Bible says in study notes on this latter passage: “In what manner will Christ come back? The event will be unmistakable to the whole world. If there is any question or doubt, that alone is evidence that He has not returned.”

Where Does This Leave Us in Determining Who Gholshiri is?

Thus, Gholshiri is not Jesus Christ returned. What’s left? He’s either the Mahdi or the Deceiving Messiah, the Antichrist. Since the Mahdi is actually a warlord, and cannot do miracles, odds are Gholshiri will turn out to be the Dajjal. One final scene may turn out to be pivotal. In that Texas town, post-tornado, a father and his son are looking for their dog. They finally find it, a black shepherd, trapped under rubble. Before they can free the animal, or put it down, Gholshiri appears, takes the shotgun from the father — and kills the dog. The boy says, “you were supposed to save him.” The alleged messiah replies, “no I wasn’t. He’s not suffering now.” According to hadiths, Muhammad hated dogs — and black ones in particular. Whether this is supposed to show Gholshiri as a pious Muslim, or evil — or perhaps both — remains to be seen.

Timothy Furnish holds a Ph.D. in Islamic, World and African history. He is a former U.S. Army Arabic linguist and, later, civilian consultant to U.S. Special Operations Command. He’s the author of books on the Middle East and Middle-earth; a history professor; and sometime media opiner (as, for example, on Fox News Channel’s “War Stories: Fighting ISIS“).