Interview With Director Laura Waters Hinson on the Painting Protestant ‘Mother Teresa of Algeria’

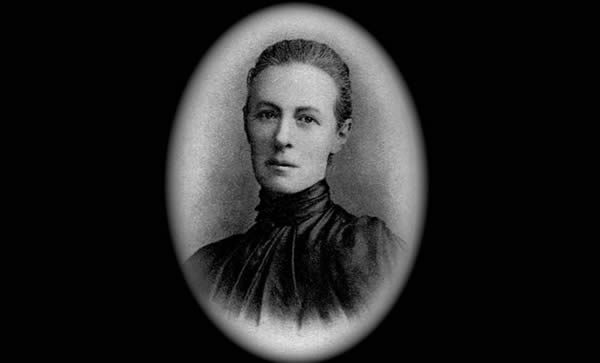

Laura Waters Hinson makes films that get noticed. Her debut effort As We Forgive won a Gold Medal at the Student Academy Awards. Dog Days, a documentary on immigrant street vendors was recently broadcast nationally. And just a few days before our interview, Many Beautiful Things: The Life and Vision of Lilias Trotter played to a packed house as part of the National Gallery of Art’s film series. Though relatively unknown today, Trotter was an inspiration to later missionaries including Elisabeth Elliot.

Under the watchful eye of Theodore, the second-hand mounted caribou that oversees operations at Image Bearer Pictures, The Stream’s John Murdock sat down with the filmmaker to talk about Christians and the arts, working with Michelle Dockery, and how the story of a young nineteenth-century woman who left the prospect of fame to serve the Arab people can still speak to us today.

Stream: Most people have never heard of your latest film’s subject. So, just who was Lilias Trotter?

Laura Waters Hinson: Lilias Trotter was a Victorian Age painter in England. She was the protégé of John Ruskin — who was at the time a very famous philosopher, art critic, writer, professor at Oxford — and he took her under his wing. But when she got into her 20s, she started ministering to the poor of London and this frustrated Ruskin. He began to feel that her work was suffering because of her divided heart. So, he basically gave her an ultimatum: I can make you one of England’s greatest painters; I think you have the ability to do things that are “immortal,” he said, but you must abandon everything to your art.

Stream: Well, what happened?

LWH: This was the great crisis of her life. Ultimately, as much as she was flattered and flabbergasted that he was offering her this, I think she felt a deep calling in her heart to not walk away from the work with the women and the poor of London. So she ultimately said “no” to Ruskin’s offer. About ten years later, she felt that there was a stirring in her soul to go to North Africa as a single woman. And she actually went on her own dime. Lilias had inherited quite a bit of money, and she was turned down by all the missions boards of the day because she apparently had some type of heart issue. So, she and a couple of friends trucked off in their early 30s to Algeria.

Stream: Algiers seems a rather alien place for a well-to-do English woman to just parachute into. How did that go?

LWH: One thing I was really drawn to in Lilias was how she came in and assimilated. She got to know the language and developed deep friendships, especially the women in the kasbah. And she taught them to read and taught them job skills because so often these women would be cast out of the harems. Husbands would divorce them for younger wives. It was a tough place to be in the late 1800s as a woman. And so she was really equipping them to manage without the support of a husband. She had a holistic way of doing ministry and continued her art at the same time. We call her the unsung Mother Teresa of Algeria.

Stream: In our day we see Christians and Muslims experiencing tensions caused by fears of terrorism and discrimination. Are there things we can learn from Trotter’s experience?

LWH: Oh, my goodness, absolutely. Lilias loved the Arab people. She came in and became a sister to those that she disagreed with. She came in and learned from them, listened to them. She did not come in with a mentality of doing battle with these people. She came in to love them. And I think her example of working with the Sufi mystics was one of the coolest things. She was able to establish such a deep friendship with them that they invited her in as a woman. The brotherhood of the Sufi mystics invited her in to talk about God. And they talked about God together, and they talked openly and peacefully. They had two very different perspectives, but they respected one another. Yes, they tried to convince each other that their way was the right way, but she did so in love and with deep respect and a genuine appreciation for their culture. I think that sets her apart. In reading her journals, there was a humility in the way she interacted with them. I think we could all learn from the way Lilias went about her work with people who were very different.

Stream: Using traditional measures of success, though, she wasn’t very successful in her lifetime.

LWH: The movie challenges our ideas about what is the true measure of success. For Lilias, even though she got discouraged at different points, she always seemed to reorient herself to what really mattered. It wasn’t about numbers and outward success. It was about being faithful, having that faithful presence daily in the people’s lives where she was. She wasn’t judging success the way we would judge success. What’s interesting is that today there are anywhere from 50,000 to 75,000 Christians in Algeria — all “underground” because Christianity is illegal. I was speaking to a former missionary from Algeria the other night, and this contact said that, absolutely, Lilias laid the groundwork for that whole movement of maybe now 500 churches. Here it is 90-something years after her death and there are thousands of Christians there in Algeria who probably wouldn’t be there if she hadn’t laid the groundwork.

Stream: One of the people in your film describes Trotter’s work as “water poured out and immediately sucked up by the desert” but maybe what you are saying is that the water filtered down and helped to fuel an aquifer that is still being tapped.

LWH: Oh, I like that. It became like groundwater. It seeped way down. She never saw a visible church in her lifetime, but there are probably a few people living as underground Christians today who knew her as children. I’ve talked to missionaries there who have met these people that remember her as their “Loving Lilias” or “La-La-Lily.” They say she loved them and she taught them to read. So, she has a legacy there, but it’s a hidden legacy. It’s hidden in the hearts of people who are Christians illegally today.

Stream: It is an amazing story and you visualize it so well in the film. Plus, the voice of Lilias is one that many people will recognize as belonging to the fictional Lady Mary. How did that happen?

LWH: I, like most of America, love Downton Abbey. When we first thought, “Who should be the voice of Lilias Trotter?” the first person that came to my mind was Michelle Dockery. She has a depth and resonance to her voice that is both authoritative and graceful. That’s how I’ve always imagined Lilias — as both this lover of beauty and this indefatigable woman who braved sandstorms on camelback alone in the desert for decades. Like, who does that?! We reached out to Dockery’s agent with the script and the rough cut, and that same week we got a reply that she wanted to do it.

Stream: Did you think it would be so easy to get her on board?

LWH: I was surprised in a way that she wanted to do it because I assume she doesn’t want to be typecast as a Victorian character for her whole life. But Michelle told me she loved the character and that she was drawn to the humility and the self-sacrifice of Lilias. She eschewed fame, she eschewed all the things that world values in exchange for this life where she served other people, and Michelle Dockery was just so impressed by this. And I should say that in real life she is so totally the opposite of her character on Downton. She is extremely humble, thoughtful, and was so prepared.

Stream: Trotter seems to have embraced sacrifice, something we are slow to do today. What can we learn from her decision to give up something good for what she saw to be the best?

LWH: For Lilias, one of the major themes of her life was that it is better to give than to receive. My favorite quote of hers is this:

Measure thy life by loss, and not by gain. Not by the wine drunk, but by the wine poured forth. For love’s strength standeth in love’s sacrifice, and he who suffers most has most to give.

And that is so the opposite of our whole ethos as a culture today — that she measured her life by her losses. By loss she means what she gave, what she gave up. She loved this imagery of the dandelion and painted it again and again — the idea that a flower is not just intended for its beauty at the peak of its bloom but that its true legacy is when it dies its seed is taken by the wind and is planted elsewhere and new life springs up. And that is how she viewed her life, as that dandelion whose seeds were being blown. She wouldn’t know where they would land, and yet she trusted that one day new life would come. And that is so different than how we view our lives. That’s probably the most challenging thing for me personally — to trust what you can’t see.

Stream: That’s the definition of faith isn’t it?

LWH: Exactly. (Laughs) To trust what you can’t see. So, I love those images whenever I’m personally feeling, “No one’s ever going to watch this thing. What I am doing this for?” I think all artists feel this way, falling into the depths of despair at times feeling that all your work is for naught. It’s so insidious. You want that external recognition and affirmation. Now in the back of my head I have this: “Measure thy life by loss, not by gain.” It’s in there now permanently, hopefully, reminding me of what really matters.

John Murdock teaches at the Handong International Law School and has written for First Things, Christianity Today, and Touchstone among others. He exists online at johnmurdock.org. Many Beautiful Things is now available on DVD and for download. (This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)